Boulenger’s Stub-foot Toad (Atelopus boulengeri)

Boulenger’s Stubfoot Toad was described in 1904, the species is known from only six places in the provinces of Morona-Santiago and Loja in the eastern Andes of Ecuador, where it was last seen in 1984.

The reasons for the disappearance of this species are the same as for most of the other extinct amphibian species: habitat loss and the fungal disease chytridiomycosis.

Boulenger’s Stubfoot Toad is now most probably extinct.

*********************

edited: 10.09.2019

Tag Archives: Ecuador

Peperomia parvilimba C. DC.v

Small-limbed Peperomia (Peperomia parvilimba)

This species was only recorded once in the early 20th century near the Río Santiago in the Esmeraldas Province of Ecuador.

The species was apparently not found since and might be extinct.

*********************

edited: 20.09.2020

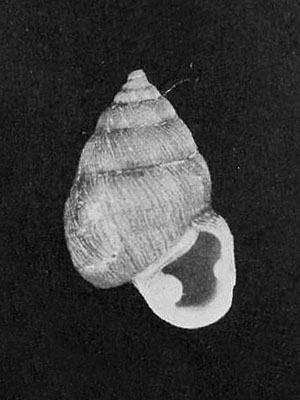

Naesiotus sp. ‘nilsodhneri’

Nils Odhner’s Galapagos Snail (Naesiotus sp. ‘nilsodhneri’)

Nils Odhner’s Galapagos Snail was described in 1985, its species epithet, however, is now considered a nomen nudum.

The species was restricted to the arid zones in the south-east of Isla Santa Cruz in the Galápagos archipelago; it was not found alive during the last recent field surveys and is now feared to be extinct.

*********************

References:

[1] Guy Coppois: Etude de la spéciation chez les Bulimulidae endémiques de l’archipel des Galápagos (Mollusques, Gastéropodes, Pulmonés). Thèse de Doctorat, Libre de Bruxelles 1-283. 1985

*********************

edited: 01.06.2021

Arenaria radians Benth.

Radiated Sandwort (Arenaria radians)

The Radiated Sandwort was endemic to Ecuador, where it apparently was restricted to the vicinity of the Chimborazo volcano.

The species is known from the type material only which was collected in 1841 or 1842, there is, however, some additional material, which, despite being very similar, seems not to belong to that species.

The Radiated Sandwort may be extinct, or may be identical with another species, Arenaria dicranoides Kunth.

*********************

edited: 14.04.2019

Euphorbia quitensis Boiss.

Quito Spurge (Euphorbia quitensis)

The Quito Spurge is known only from two collections, the first one from 1862 and the other one from 1887, the species was found in mountain forests at elevations of 2500 to 3000 m on the western slopes of the Andes.

The species was never recorded since and is very likely already extinct.

*********************

edited: 21.01.2019

Miconia longisetosa Wurdack

Long-bristled Miconia (Miconia longisetosa)

The Long-bristled Miconia is known exclusively from the type material that was collected in 1886 on the western slopes of the Pichincha volcano in the Pichncha Province of Ecuador.

The species was never recorded again and is feared to be extinct.

*********************

edited: 28.01.2020

Guzmania lepidota (Andrè) Andrè ex Mez

Scaly Guzmania (Guzmania lepidota)

This epiphytic species is known only from the type collection that was found in 1876 in dense Andean forest at the base of the Pululahua volcano in the Pichincha Province of Evcuador.

The species has never been recorded since and is very likely extinct.

***

The Scaly Guzmania was superficially quite similar to the closely related Many-flowered Guzmania (Guzmania multiflora (André) André ex Mez) (see photo below), which is occurring in Colombia and Ecuador.

*********************

Photo: coqwallon

https://www.inaturalist.org/people/coqwallon

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

*********************

edited: 25.02.2024

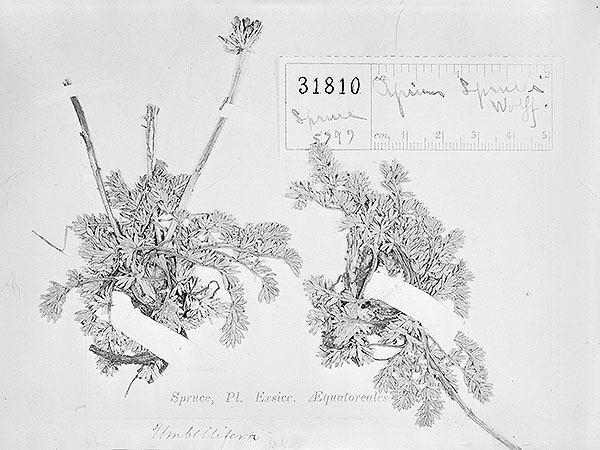

Niphogeton sprucei (H. Wolff) Mathias & Constance

Spruce’s Niphogeton (Niphogeton sprucei)

Spruce’s Niphogeton is endemic to Ecuador; it is only known from two collections, the first one collected sometime between 1857 to 1860 and the second one between 1826 to 1873.

The species has never been found since and is quite well extinct today.

*********************

Photo: Field Museum of Natural History (F: Botany)

https://herbariovaa.org

(under creative commons license (3.0))

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/

*********************

edited: 14.05.2022

Hypericum hartwegii Benth.

Hartweg’s St. John’s Wort (Hypericum hartwegii)

Hartweg’s St. John’s Wort was described in 1843, it is apparently known only from the type material that was collected in 1841 near the city of Chuquiribamba in the Loja Province of Ecuador.

The species was never recorded again since and is likely extinct.

*********************

edited: 03.11.2020

Piper wibomii Yunck.

Wibom’s Pepper (Piper wibomii)

Wibom’s Pepper was found only near the town of Quinindé east of the Río Blanco in the province Esmeraldas, Ecuador, a region that is now more or less completely deforested and transformed into farmland.

According to different sources this species is/was either a climbing liana or a tree.

*********************

edited: 27.11.2018

Peperomia dauleana C. DC.

Rio Daule Peperomia (Peperomia dauleana)

The Rio Daule Peperomia was only ever found once sometimes in the 19th century near the Río Daule in the Guayas Province, Ecuador.

The habitat of the locality is now almost completely destroyed and the species is very likely extinct.

*********************

edited: 20.09.2020

Atelopus planispina Jiménez de la Espada

Napo Stub-foot Toad (Atelopus planispina)

The Napo Stub-foot Toad was described in 1875, the species was found very abundantely near a place named San José de Moti, which today is named San José de Mote in the Napo Province of eastern Ecuador, it inhabited humid montane forests at elevations of 1000 to 2000 m.

The species fed on beetles, insect larvae and even scorpions (based on the dissection of at least one sindividual). [1]

The Napo Stub-foot Toad was last seen in 1985, it appears to have be among the first amphibian species that have disappeared due to the deadly fungal chytridiomycosis disease.

*********************

References:

[1] Marcos Jiménez de la Espada: Vertrebrados del viaje al Pacifico : verificado de 1862 a 1865 por una comisión de naturalistas enviada por el Gobierno Español. Madrid: M. Ginesta 1875

*********************

edited: 10.09.2019

Psychotria acutiflora DC.

Sharp-leaved Psychotria (Psychotria acutiflora)

The Sharp-leaved Psychotria is or was restricted to the dry coastal forests in the Guayaquil area in the Guayas Province, Ecuador.

The species was not found again and might well be extinct.

*********************

edited: 03.09.2020

Chelonoidis sp. ‘Santa Fé’

Santa Fe Tortoise (Chelonoidis sp.)

The Isla Santa Fé, also known as Barrington Island, is a small, only about 24 km² large island, but may very well have once harbored its own endemic population of tortoises.

There are three reasons to assume the former existence of a local population.:

Firstly: Contemporaneous accounts by settlers and whalers, the latest of which dating from 1890, which also mention tortoise hunts on the island.

Secondly: Subfossil and recent tortoise bones are well known from the island, yet no part of a carapace is known, thus the exact status of these remains cannot be ascertained.

However, tortoises were transported in the 19th century from one island to another, without any kind of registering, thus these two abovementioned reasons may in fact also apply to a imported tortoise population. But there is still the third and best reason ….

Thirdly: By far the best evidence for the former existence of a endemic tortoise population comes from the island’s flora – the Barrington Island Tree Opuntia (Opuntia echios var. barringtonensis E. Y. Dawson) is an endemic variety of the typical tree-like opuntias that have evolved only on islands with tortoises, while the opuntia forms on tortoise-free islands are always growing as low creeping bushes, because, in the absence of large herbivorous tortoises they just did not need to develop a trunk.

Thus there simply must have been a local race or species of tortoise on the Isla Santa Fé!

***

In spite of everything, the Santa Fe Tortoise is still officially regarded as a hypothetical form.

*********************

References: [1] Dennis M. Hansen; C. Josh Donlan; Christine J. Griffiths; Karl J. Campbell: Ecological history and latent conservation potential: large and giant tortoises as a model for taxon substitutions. Ecography Vol. 33(2) 272–284. 2010

*********************

edited: 26.07.2013

Gonzalagunia bifida B. Ståhl

Split Gonzalagunia (Gonzalagunia bifida)

This species is known from the type collection from 1968 and another collection that was made somewhat later.

The species was not found since and may be extinct.

*********************

edited: 12.01.2019

Myotis diminutus Moratelli & Wilson

Small Whiskered Bat (Myotis diminutus)

This species was described in 2011 and was originally known only from the type, a subadult individual that had been collected in 1979 in a fragment of moist forest on the western slopes of the Ecuadorian Andes.

A second specimen, discovered some years later in a museum collection was collected in 1959 at La Guayacana in western Colombia.

The Small Whiskered Bat apparently is/was restricted to the so-called Chocó ecoregion, lowland forest areas that now are mostly deforested, and is probably extinct. [1]

*********************

References:

[1] Ricardo Moratelli; Don E. Wilson: A second record of Myotis diminutus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae): its bearing on the taxonomy of the species and discrimination from M. nigricans. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 127(4): 533-543. 2015

*********************

edited: 13.01.2019

Nesoryzomys sp. 2 ‘Isla Isabela’

Isabela Rice Rat (Nesoryzomys sp.)

This is one of two species of rice rats that formerly were endemic to the Isla Isabela in the Galápagos Islands, it disappeared sometimes during the middle 19th to the early 20th century.

*********************

edited: 11.06.2020

Naesiotus trogonius (Dall)

Volcano Galapagos Snail (Naesiotus trogonius)

This species was described in 1917, it is endemic to Isla Isabela in the Galápagos archipelago, where it is thought to have inhabited the forests on the slopes of the volcano Ecuador.

The species was not found alive since the 1800s and is definitely extinct.

***

syn. Bulimulus trogonius Dall

*********************

References:

[1] William Healey Dall; Washington Henry Ochsner: Landshells of the Galapagos Islands. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences. Ser. 4. Vol. 17.: 141-185. 1928

*********************

edited: 01.06.2021

Naesiotus sp. ‘vanmoli’

Van Mol’s Galapagos Snail (Naesiotus sp. ‘vanmoli’)

Van Mol’s Galapagos Snail was described in 1985, its species name is now considered a nomen nudum, however.

The species was endemic to the southwestern part of the island of Santa Cruz in the Galápagos archipelago, where it was found in a narrow area only some 600 m wide in the arid zone at an altitude of about 65 m above sea level. [1]

Van Mol’s Galapagos Snail has not been found during the last field searches; it is thus believed to be most likely extinct.

*********************

References:

[1] Guy Coppois: Etude de la spéciation chez les Bulimulidae endémiques de l’archipel des Galápagos (Mollusques, Gastéropodes, Pulmonés). Thèse de Doctorat, Libre de Bruxelles 1-283. 1985

*********************

edited: 01.06.2021

Naesiotus sp. ‘josevillani’

Jose Villan’s Galapagos Snail (Naesiotus sp. ‘josevillani’)

Jose Villan’s Galapagos Snail was described in 1985, its species epithet, however, is now considered a nomen nudum, the reasons therefore are not known to me.

The species was endemic to the Isla Santa Cruz in the Galápagos archipelago, where it was found in the Scalesia forests of the higher altitudes. [1]

Jose Villan’s Galapagos Snail hasn’t been found during the most recent field searches and is thus considered very likely extinct.

*********************

References:

[1] Guy Coppois: Etude de la spéciation chez les Bulimulidae endémiques de l’archipel des Galápagos (Mollusques, Gastéropodes, Pulmonés). Thèse de Doctorat, Libre de Bruxelles 1-283. 1985

*********************

edited: 01.06.2021

Naesiotus sp. ‘deridderi’

De Ridder’s Galapagos Snail (Naesiotus sp. ‘deridderi’)

This species was described in 1985, its species epithet, however, is a nomen nudum.

De Ridder’s Galapagos Snail occurred in the moister regions of the island of Santa Cruz; the animals apparently had a certain preference for the Arrow-leaved Sida (Sida rhombifolia L.) or the Prickly Sida (Sida spinosa L.), on whose branches they were often found. [1]

The species was not found alive during the last recent field studies and is feared to be extinct.

***

One of the few natural enemies of this species was the Woodpecker Finch (Camarhynchus pallidus (Sclater & Salvin)), which is known to occasionally pick up snails from the plants, which it subsequently beats against a twig or the like until the snail’s body detaches from the shell.

The reason for the extinction of so many of the endemic snail species of the Galápagos Islands, however, is mainly due to the destruction of their habitats.

*********************

References:

[1] Guy Coppois: Etude de la spéciation chez les Bulimulidae endémiques de l’archipel des Galápagos (Mollusques, Gastéropodes, Pulmonés). Thèse de Doctorat, Libre de Bruxelles 1-283. 1985

[2] G. Coppois: Threatened Galapagos bulimulid land snails: an update. In: E. Alison Kay: The Conservation Biology of Molluscs. Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commision 9: 8-11. 1995 [3] C. E. Parent; R. P. Smith: Galápagos bulimulids: status report on a devastated fauna. Tentacle 14. 2006

[4] C. E. Parent; B. J. Crepsi: Sequential colonization and diversification of Galapágos endemic land snail genus Bulimulus (Gastropoda, Stylommatophora). Evolution 60(11): 2311-2328. 2006

*********************

edited: 01.06.2021

Viguiera media S. F. Blake

The Medium Goldeneye is, or maybe was, a terrestrial herb that is known only from the type material which had been collected in 1849 near the city of Nabón in the Azuay Province of Ecuador.

The locality is now highly reduced resp. degraded and the species might well be extinct.

*********************

edited: 05.05.2022

Blutaparon rigidum (B. L. Rob. & Greenm.) Mears

Santiago Amarant (Blutaparon rigidum)

This species is known only from two collections that were made in 1905 and 1906 on the Isla Santiago in the Galápagos Islands.

The Santiago Amaranth was very well adapted to the dry habitats of its home island, it was a small profusely and compactly branched shrub and had small, needle-like leaves. [1]

The species disappeared due to the appetite of introduced donkeys, pigs and especially goats, whose numbers on Isla Santiago alone were estimated in 1980 as being as high as 80000 to 100000! [2]

*********************

References:

[1] I. Loren Wiggins; D. M. Porter; E. F. Anderson: Flora of the Galápagos Islands. Stanford University Press 1971

[2] F. Cruz; V. Carrion; K. J. Campbell; C. Lavoie; C. J. Donlan: Bio-Economics of Large-Scale Eradication of Feral Goats from Santiago Island, Galápagos. The Journal of Wildlife Management 72(2): 191-200. 2009

*********************

edited: 11.06.2020

Wedelia oxylepis (S. F. Blake)

Guayaquil Oxeye (Wedelia oxylepis)

This species is known only from the typus material, which was collected in the year 1918 near the city of Guayaquil in the Ecadorian province of Guayas.

The natural vegetation in this area is now nearly completely destroyed, and therefore the Guayaquil Oxeye is most probably extinct.

*********************

edited: 17.05.2019

Guzmania poortmanii (Andrè) Andrè ex Mez

Poortman’s Guzmania (Guzmania poortmanii)

This epiphytic species was described in 1889; it is apparently only known from the type material that had been collected at what today is the city of Lauro Guerro in the Loja Province of Ecuador.

The species has never been found since and is apparently extinct.

***

The photo below shows a congeneric species also occurring in Ecuador, Weberbauer’s Guzmania (Guzmania weberbaueri Mez).

*********************

Photo: Alan Rockefeller

https://www.inaturalist.org/people/alan_rockefeller

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

*********************

edited: 25.02.2024

Vittaria longipes Sodiro

Long-footed Ribbon Fern (Vittaria longipes)

This species is only known from the type material collected in the Nanegal Valley in the Pichincha Province of Ecuador.

The place where it was found has meanwhile been changed to a great extent by agriculture etc., and this species very likely is extinct.

*********************

edited: 30.04.2021

Amsinckia marginata Brand

Marginated Amsinckia (Amsinckia marginata)

This species is known from the type material that was collected sometimes at the beginning of the 20th century near Quito in the Pichincha Province of Ecuador.

The species was never recorded since and might well be extinct.

*********************

edited: 30.04.2021

Salvia lobbii Epling

Lobb’s Sage is known only from the type material that was collected sometimes before 1936, apparently somewhere in Ecuador (or maybe Peru).

Nothing else is known about this species and it might well be extinct.

*********************

edited: 13.08.2022

Atelopus arthuri Peters

Arthur’s Stub-foot Toad (Atelopus arthuri)

Arthur’s Stub-foot Toad was described in 1973, this beautiful littles species occurred in moist montane forests at three localities in the Andes of the Chimborazo Province, Ecuador.

The species was last recorded in 1988, it was never seen since and is now considered most certainly extinct, the reason for its disappearance is the deadly chytridiomycosis fungal disease, caused by the fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis Longcore, Pessier & D. K. Nichols..

*********************

www.anfibioswebecuador.ec

(by courtesy of Néstor Acosta)

*********************

edited: 10.09.2019

Phyllanthus millei Standl.

Mille’s Phyllanthus is known exclusively by its type material which was collected in 1938 somewhere in the coastal dry forest in the Manabí Province of Ecuador.

The species has never been found since and might well be extinct.

*********************

edited: 13.08.2022

Polypodium rimbachii Sodiro

Rimbach’s Polypody (Polypodium rimbachii)

Rimbach’s Polypody is apparently known only from bibliographic references that were given to the type, which again was collected at a place named Quinoas in the Azuay Province of Ecuador and wich apparently is now lost.

The area from where the type material was collected is now very affected by deforestation and the species, if it was one, may indeed be extinct.

*********************

edited: 15.04.2019

Chelonoidis abingdonii (Günther)

Pinta Island Tortoise (Chelonoidis abingdonii)

This species was described in 1877, it was endemic to the somewhat isolated Isla Pinta aka. Abingdon Island in the northern part of the Galápagos archipelago.

The species was thought to be extinct, when in 1971, a last individual was located, it was a male that was named ‘Lonesome George’ and was relocated to the Charles Darwin Research Station on Isla Santa Cruz for his safety.

Several attempts at mating Lonesome George with females of other tortoise species were unsuccessful, possibly because his species was not cross-fertile with the other species.

***

Lonesome George (see photo), the last member of its species, died at 24 June 2012.

***

It seems that there are still some individuals in existence that at least harbor some DNA of this extinct species within their blood.

*********************

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/

*********************

edited: 01.06.2021

Piper platylobum Sodiro

Many-lobed Pepper Treelet (Piper platylobum)

This species was restricted to mountain forest at the western slopes of the Andes in the province Pichincha, Ecuador, where it was found at elevations between 1000 and 1600 m.

The species is known exclusively from a single collection from the year 1898 and is most likely already extinct.

*********************

edited: 27.11.2018

Hieracium coloratum Arv.-Touv.

Colored Hawkweed (Hieracium coloratum)

The Colored Hawkweed was collected more than 120 years ago in the “Andibus Ecuadorensibus“, an exact locality was not given.

The species was never found since and might well be extinct.

*********************

edited: 02.10.2020

Pyrocephalus dubius Gould

San Cristobal Flycatcher (Pyrocephalus dubius)

The Vermilion Flycatcher (Pyrocephalus rubinus (Boddaert)), probably the most colorful of the tyrant flycatchers, has several subspecies that are distributed over nearly all of South- and Central America. The two forms that occur on the Galápagos archipelago, however, are now treated as distinct species. [1]

***

The Little Vermilion Flycatcher, also known as Darwin’s Flycatcher (Pyrhocephalus nanus Gould) (see depiction below), is endemic to the Galápagos Islands, where it is widely distributed especially at the higher elevations, it does, however, not occur on Isla San Cristóbal, where the San Cristobal Flycatcher occurs, or rather did occur.

The birds from Isla San Cristóbal differed from those of the other islands in their coloration. The males had a paler brown plumage, they had a paler red colored underside and a darker red crown. The females had a striking eye stripe, the underside was strong ocher to light rust colored, the throat was a little lighter ocher colored.

The San Cristobal Flycatcher apparently was last restricted to the very dry areas along the western coast of the island and were recorded as being extremely rare in the 1980s when large amounts of the native vegetation had been replaced by invasive plant species which again led to the disappearance of the native insect fauna which the birds fed upon.

The last record dates to 1987.

The San Cristobal Flycatcher was never seen since and is now considered most likely extinct.

*********************

References:

[1] Ore Carmi; Christopher C. Witt; Alvaro Jaramillo; John P. Dumbacher: Phylogeography of the Vermilion Flycatcher species complex: Multiple speciation events, shifts in migratory behavior, and an apparent extinction of a Galápagos-endemic bird species. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 102: 152-173. 2016

*********************

Depiction from: ‘John Gould: The Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle, under the command of Captain Fitzroy, during the years 1832-1836. Part III, Birds. London, Smith, Elder & Co. 1838’

(public domain)

*********************

edited: 11.06.2020

Peperomia pululaguana C. DC.

Pululahua Peperomia (Peperomia pululaguana)

The Pululahua Peperomia is known from only two populations, which both were last recorded more then 100 years ago, one on the slopes of the Pichincha Volcano and the other one on the slopes of the Pululahua Volcano both in the Pichincha Province, Ecuador.

The species apparently was not found in recent decades and might be extinct.

*********************

edited: 20.09.2020

Guatteria microcarpa Ruiz & Pav. ex G. Don

The Small-seeded Guatteria is known from a herbarium specimen that was collected near Guayaquil, the capital of the Guayas Province of Ecuador sometimes between 1788 and 1788, as well as from a second specimen, which again was collected about a century later

The species was not found recently and is very likely extinct.

*********************

Depiction from: ‘H. Ruiz López; J. A. Pavón: Flora Peruviana, et Chilensis. Vol. 4-5. Anales del Instituto Botánico A.J. Cavanilles. Vol. 12-16. 1954-1959

(under creative commons license (4.0))

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

*********************

edited: 13.11.2021

Peperomia stenostachya C. DC.

Thick-spined Peperomia (Peperomia stenostachya)

This species known from a single collection purchased at the flanks of the Pichincha Volcano in the Pichincha Province, Ecuador.

The species was apparently not found since and might now be extinct.

*********************

edited: 20.09.2020

Dicliptera quitensis Mildbr.

Quito Dicliptera (Dicliptera quitensis)

This terrestrial, herbaceous plant is known only from the type material which was collected in 1933 on a river bank in the vicinity of the city of Quito, the capital of Ecuador.

The species was never found again since and is almost for certain extinct.

*********************

edited: 19.06.2020

Miconia benoistii Wurdack

Benoist’s Miconia (Miconia benoistii)

This species is known from the type material that was collected in 1930 at the base of the Pichincha volcano in the Pichincha Province of Ecuador, however, an exact locality seems not to be known.

The species was never recorded since and might be extinct.

*********************

edited: 28.01.2020

Diplazium corderoi (Sodiro) Diels

Cordero’s Diplazium Fern was described in 1899; it is known only from the banks of the Río Peripa in the Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas Province of Ecuador.

This sole known locality is nowadays totally altered by the Daule-Peripa dam and by the use of the land for the cultivation of bananas and cocoa, thus the species might well be extinct.

***

However, there is also the possibility that this fern was in fact misidentified and that it is still around.

*********************

edited: 09.08.2022

Atelopus angelito Ardila-Robayo & Ruíz-Carranza

The Angelito Stub-foot Toad was described in 1998; it is known from two localities, one in Colombia and the other one in northern Ecuador (only based on museum specimens).

The species is beautifully green colored with a rather yellowish green under side.

The Angelito Stub-foot Toad was already nearly extinct when it was described and only few specimens were found; it was last recorded in 2000 and appears to be extinct now.

*********************

References:

[1] Luis A. Coloma; William E. Duellman; Ana Almendáriz C.; Santiago R. Ron; Anrea Terán-Valdez; Juan M. Guayasamin: Five new (extinct?) species of Atelopus (Anura: Bufonidae) from Andean Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru.

Zootaxa 2574: 1-54. 2010

*********************

edited: 17.08.2022

Naesiotus blombergi (Odhner)

Blomberg’s Galapagos Snail (Naesiotus blombergi)

Blomberg’s Galapagos Snail was described in 1950 (or 1951 according to other sources) based on 12 specimens that were collected 200 to 300 m above sea level on plants, bushes and trees on the Isla Santa Cruz in the Galápagos archipelago. [1]

The species was apparently last seen alive in 1974; it was not found during the most recent field surveys and is feared to be extinct.

*********************

References:

[1] Steven M. Chambers; David W. Steadman: Holocene terrestrial gastropod faunas from Isla Santa Cruz and Isla Floreana, Galápagos: evidence for late Holocene declines. Transactions of the San Diego Society of Natural History 21(6): 89-110. 1986

*********************

edited: 01.06.2021

Naesiotus adelphus Dall

Adelphus’ Galapagos Snail (Naesiotus adelphus)

Adelphus’ Galapagos Snail, described in 1917, is endemic to the Isla Santa Cruz, Galápagos Islands, where it inhabited the island’s arid zones. [1]

***

Robert P. Smith, a gastropod specialist, investigated the snail populations on six of the larger islands of the Galápagos archipelago in 1970, including Isla Santa Cruz. By 2005 and 2005, when exactly the same areas were investigated again, many populations had disappeared.

The touristic industry is booming on the islands, particularly on Isla Santa Cruz, and many of the former habitats are destroyed today, not only by development but also by the introduction of foreign species (animals and plants).

The highlands, formerly home to endemic species like the Galapagos Miconia (Miconia robinsoniana Cogn.) and the Santa Cruz Scalesia (Scalesia pedunculata Hook. F.) are now overrun by introduced plant species, just like the lower regions of the island are.

The snails are also killed by introduced ants, especially by the Little Fire Ant, also known as Electric Ant, (Wasmannia auropunctata (Roger)). [2][3]

***

Adelphus’ Galapagos Snail was not found in recent years, despite specific searches, and is considered most likely extinct.

*********************

References:

[1] William Healey Dall; Washington Henry Ochsner: Landshells of the Galapagos Islands. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences. Ser. 4. Vol. 17.: 141-185. 1928

[2] Christine E. Parent; Robert P. Smith: Galápagos bulimulids: status report on a devastated fauna. Tentacle 14. 2006

[3] Christine E. Parent; Bernard J. Crepsi: Sequential colonization and diversification of Galapágos endemic land snail genus Bulimulus (Gastropoda, Stylommatophora). Evolution 60(11): 2311-2328. 2006

*********************

(under creative commons license (3.0))

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

*********************

edited: 01.06.2021

Hieracium debile Fr.

Weak Hawkweed (Hieracium debile)

The Weak Hawkweed is known only from two collections that were made at the end of the 19th century somewhere in Ecuador.

The species might well be extinct.

*********************

edited: 02.10.2020

Miconia scabra Cogn.

Rough Miconia (Miconia scabra)

The Rough Miconia is known exclusively from the type material that was collected in the year 1876 somewhere at the Chimborazo volcano in the Chimborazo Province of Ecuador.

The area where this species is thought to have been fpund is quite frequently visited by botanists, however, this species was never found again and is now considered most likely extinct.

*********************

edited: 28.01.2020

Sicyos villosus Hook. f.

Galapagos Bur Cucumber (Sicyos villosus)

This species is only known from the type material, which was collected in the year 1853 by Charles Darwin on the island of Floreana. He wrote the following note on his herbaria sheet.:

“… in great beds injurious to vegetation ….”

Therefore, the Galapagos Bur Cucumber obviously was quite common at that time.

The reason for the complete extinction of this species lies, in all likelihood, in the feral goats, which until very recently could spread unfettered all over every place, on almost every single island in the Galápagos Archipelago.

***

In the year 2006, a program for the eradication of feral goats (and donkeys) was started on the island of Floreana – the same program had proved very successful over several years on other islands of the archipelago. During this campaign the number of goats shot in the year 2008 alone was 1334.

Unfortunately, goats are still illegally released on the Islands.

*********************

References:

[1] Ira Loren Wiggins; Duncan M. Porter; Edward F. Anderson: Flora of the Galápagos Islands. Stanford University Press 1971

[2] Alison Pearn: A Voyage Round the World: Charles Darwin and the Beagle Collections in the University of Cambridge. Cambridge University Press 2011

*********************

edited: 11.06.2020

Piper clathratum C. DC.

Latticed Pepper Tree (Piper clathratum)

This species was restricted to the slopes of the Pichincha volcano in the province of Pichincha in Ecuador, it appears to be known exclusively from material that was collected about one century ago.

*********************

edited: 27.11.2018

Manettia holwayi Standl.

Holway’s Manettia (Manettia holwayi)

This species is known only from the type that was collected in 1920 somewhere in the Chimborazo province of Ecuador in the Andean forests at an elevation between 1500 and 2000 m.

The species is very likely extinct.

*********************

edited: 29.11.2018

Phycodrina elegans (Setchell & N. L. Gardner) M. J. Wynne

Elegant Red Alga (Phycodrina elegans)

The elegant Red Alga was a marine algae species that was endemic to the ocean surrounding the Galápagos Islands, and it appears to have been very common in former times.

The species disappeared after or during a devastating El Niño event that took place between 1982 and 1983. However, the removal of lobsters and other fish predators from the environment by local fishers lead to a cascade of direct and indirect effects involving explosive population expansion of grazing (algae-feeding) sea urchins.

This again lead to the complete extinction of several endemic marine algae species from the waters around the Galápagos archipelago that happened almost unnoticed by the public.

*********************

References:

[1] Graham J. Edgar; Stuart A. Banks; Margarita Brandt; Rodrigo H. Bustamantes; Angel Chiriboga; Lauren E. Garske; Peter W. Glynn; Jack S. Grove; Scott Henderson; Cleve P. Hickman; Kathy A. Miller; Fernando Rivera; Gerald M. Wellington: El Niño, grazers and fisheries interact to greatly elevate extinction risk for Galapagos marine species. Global Change Biology 16: 2876-2890. 2010

(under creative commons license (3.0))

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0

*********************

edited: 29.11.2018

Piper gualeanum C. DC.

Gualea Pepper Tree (Piper gualeanum)

This species is known exclusively from material that was collected about a century ago in the Pichincha Province of Ecuador.

The Gualea Pepper Tree is one of only 10 species in its genus that bears peltate leaves.

*********************

edited: 27.11.2018

Ditaxis macrantha Pax & K. Hoffm.

Large-flowered Ditaxis (Ditaxis macrantha)

This species is known only from the type collection which was collected in the year 1897 somewhere in the Manabí Province, Ecuador.

The native vegetation in the type locality is now drastically altered.

The Large-flowered Ditaxis was never found again since and thus is very likely extinct.

*********************

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0

*********************

edited: 05.09.2020