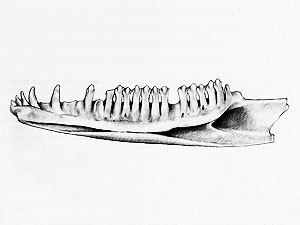

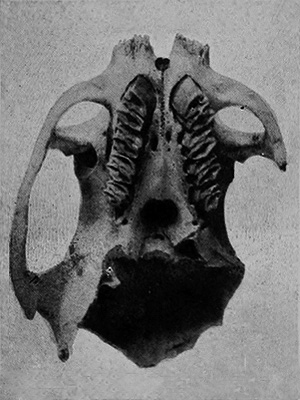

Haitian Cave Rail (Nesotrochis steganinos)

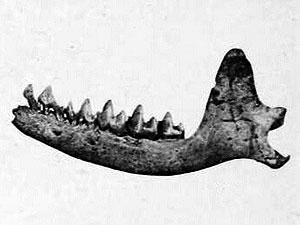

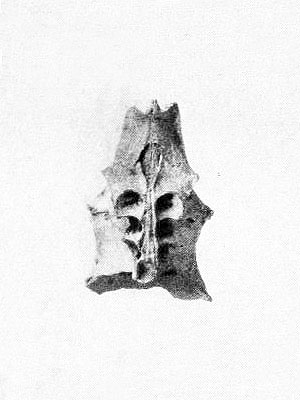

The Haitian Cave Rail was described in 1974 on the basis of subfossil remains, it is the smallest of the three species that are assigned to this genus whose relations, by the way, are still quite unknown.

The species, like its congeners, showed a remarkable sexual dimorphism.:

“There appear to be two distinct types of humeri in N. steganinos – larger ones with a shallow elongated brachial depression … and smaller ones with a very deep, rounded brachial depression …. These at first seemed so disparate that I took them to be from entirely different species. However, they are alike in all but these two respects and one of the specimens (205691) is somewhat intermediate. it seems best, therefore, to refer all of these humeri to N. steganinos, since there is no other indication of the presence of two species of Nesotrochis in the deposits. The size differences are in accord with observed size differences in the hindlimb, while differences in the brachial depression are possibly indicative of a sexual dimorphism that involved more than size.” [1]

***

The remains of the Haitian Cave Rail were found in cave deposits containing great quantities of bones of several larger, now mostly extinct rodents and other mammals which were accumulated by the likewise extinct Hispaniolan Giant Barn Owl (Tyto ostologa Wetmore). [1]

*********************

References:

[1] Storrs L. Olson: A new species of Nesotrochis from Hispaniola, with notes on other fossil rails from the West Indies (Aves: Rallidae). Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 87(38): 439-450. 1974

[2] Jessica A. Oswald; Ryan S. Terrill; Brian J. Stucky; Michelle J. LeFebvre; David W. Steadman; Robert P. Guralnick: Supplementary material from “Ancient DNA from the extinct Haitian cave-rail (Nesotrochis steganinos) suggests a biogeographic connection between the Caribbean and Old World”. Biological Letters 17(3). 2021

*********************

edited: 16.02.2020