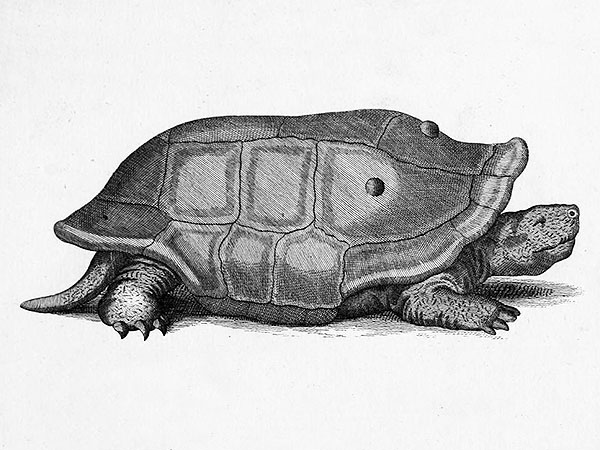

Santa Fe Tortoise (Chelonoidis sp.)

The Isla Santa Fé, also known as Barrington Island, is a small, only about 24 km² large island, but may very well have once harbored its own endemic population of tortoises.

There are three reasons to assume the former existence of a local population.:

Firstly: Contemporaneous accounts by settlers and whalers, the latest of which dating from 1890, which also mention tortoise hunts on the island.

Secondly: Subfossil and recent tortoise bones are well known from the island, yet no part of a carapace is known, thus the exact status of these remains cannot be ascertained.

However, tortoises were transported in the 19th century from one island to another, without any kind of registering, thus these two abovementioned reasons may in fact also apply to a imported tortoise population. But there is still the third and best reason ….

Thirdly: By far the best evidence for the former existence of a endemic tortoise population comes from the island’s flora – the Barrington Island Tree Opuntia (Opuntia echios var. barringtonensis E. Y. Dawson) is an endemic variety of the typical tree-like opuntias that have evolved only on islands with tortoises, while the opuntia forms on tortoise-free islands are always growing as low creeping bushes, because, in the absence of large herbivorous tortoises they just did not need to develop a trunk.

Thus there simply must have been a local race or species of tortoise on the Isla Santa Fé!

***

In spite of everything, the Santa Fe Tortoise is still officially regarded as a hypothetical form.

*********************

References: [1] Dennis M. Hansen; C. Josh Donlan; Christine J. Griffiths; Karl J. Campbell: Ecological history and latent conservation potential: large and giant tortoises as a model for taxon substitutions. Ecography Vol. 33(2) 272–284. 2010

*********************

edited: 26.07.2013