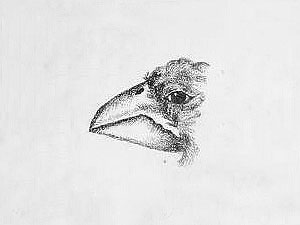

Hawaii Nukupuu (Hemignathus sp.)

The island of Hawai’i today is the home of the Akiapolaau (Hemignathus wilsoni (Rothschild)) (see depiction below), the last of the so-called hetero-billed finches, a group of Hawaiian drepenidine finches with extremely strange bills in which the lower beak is short and, depending on the species, curved up- or downwards, and the upper beak significantly longer and down curved.

This species is depicted below.

The island of Hawai’i, however, once also harbored at least two other hetero-billed finch species, namely the so-called Giant Nukupuu (Hemignathus vorpalis Olson & James), known only by subfossil remains, and the ‘actual’ Nukupuu (Hemignathus aff. lucidus), which is known by a single historical specimen, and which most certainly represented a full and endemic species.

More about this enigmatic form follows below.:

***

“Hemignathus lucidus subspp. indet.

A historic specimen of this species, of indeterminate race, was collected on the island of Hawaii by the U.S. Exploring Expedition in 1840 or 1841, but the species was never again taken on that island. A fossil almost certainly of this species was also recovered from sand dune deposits on Molokai.” [2]

The authors treat all Nukupuu forms as a single species, thus this somewhat misleading statement – the fossil from Moloka’i, of course, is more closely related to the Maui Nukupuu (Hemignathus affinis Rothschild) from Maui.

This sole Hawaii Nukupuu specimen very likely constitutes a sub-adult individual, its plumage appearing to had been in the stage of molting into a yellower garb; the dorsum, the crown and the wings are dull olive with a grayish cast; the underparts are creamy whitish; yellow feathers appear on the lower cheeks and on the midline of the throat and the sides of the upper breast, forming a sort of inverted Y; it also had a faint yellow superciliary line. [1]

This is perhaps one of the most enigmatic of the many Hawaiian drepanidine finches and is shows that these islands have lost an unimaginable precious treasure trove of diversity!

*********************

Depiction from: ‘W. Rothschild: The Avifauna of Laysan and the neighbouring islands with a complete history to date of the birds of the Hawaiian possession. 1893-1900’

(public domain)

*********************

References:

[1] Storrs Olson & Helen F. James: A specimen of Nuku pu’u (Aves: Drepanidini: Hemignathus lucidus) from the island of Hawai’i. Pacific Science 48(4): 331-338. 1994

[2] Storrs Olson & Helen F. James: Nomenclature of the Hawaiian Akialoas and Nukupuus (Aves: Drepanidini). Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 108(3): 373-387. 1995

*********************

edited: 09.10.2020