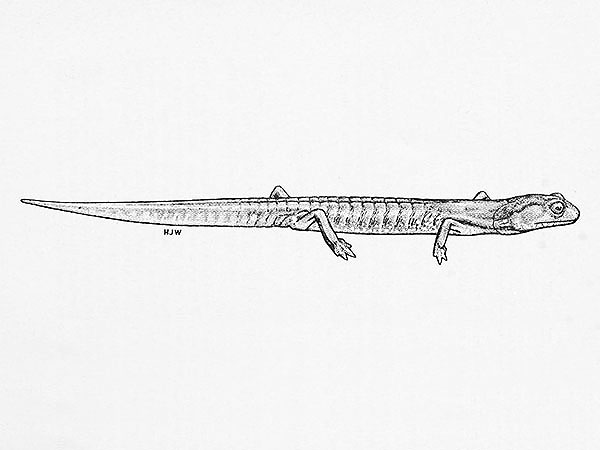

Tumbala Climbing Rat (Tylomys tumbalensis)

The Tumbala Climbing Rat was described in 1901; it is known from a single specimen that was collected from the tropical forest that formerly covered the area that today is occupied by the town of Tumbalá in Chiapas, Mexico.

The locality is now more or less completely deforested, thus the species’ habitat is lost, making the survival of the The Tumbala Climbing Rat highly improbable, it is very likely extinct.

***

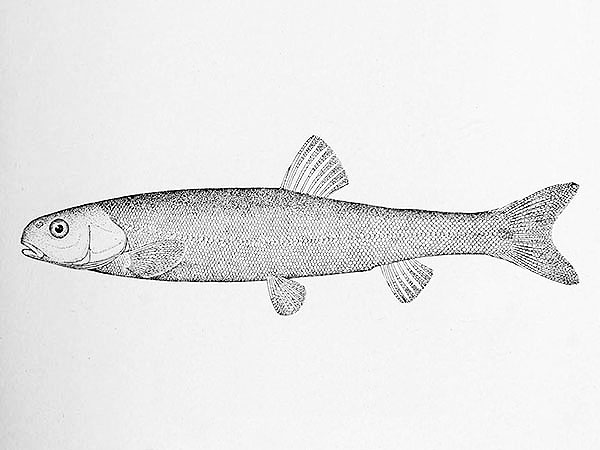

The closest relative of the Tumbala Climbing Rat is Peter’s Climbing Rat (Tylomus nudicaudus (Peters)) that is quite widespread and is found in most of Central America, it is depicted below.

*********************

Photo: Daniel Dorantes

https://www.inaturalist.org/people/danieldorantes7

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

*********************

edited: 19.02.2024