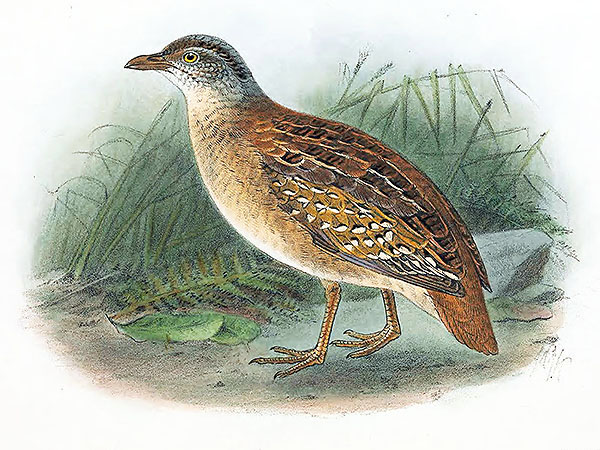

Nauru Rail (Gallirallus sp.)

“Es gibt auch Vögel auf Nauru, wie Fregattvogel, schwarze Seeschwalbe, weiße Seeschwalbe, Regenpfeifer, Brachvogel, Möve, Schnepfe, Uferläufer, Ralle, Lachmöve und Rohrdrossel.”

translation:

“There are also birds on Nauru, as frigate bird, black tern, white tern, plover, curlew, gull, snipe, sandpiper, rail, black-headed gull and reed thrush.“

and …

“Die Vogelwelt ist nach Zahl und Art reicher. Der Fregattvogel (Tachypetes aquila), itsi, die schwarze Seeschwalbe (Anous), doror, die weiße Seeschwalbe (Gygis), dagiagia, werden als Haustiere gehalten; der erste galt früher als heiliger Vogel, mit den beiden anderen werden Kampfspiele veranstaltet. Am Strande trifft man den Steinwälzer (Strepsilas interpres), dagiduba, den Regenpfeifer (Numenius), den Uferläufer (Tringoides), ibibito, die Schnepfe, ikirer, den Brachvogel ikiuoi, den Strandreiter iuji, die Ralle, earero bauo und zwei Möwenarten (Sterna), igogora und ederakui. Im Busche beobachtet man an den Blüten der Kokospalme den kleinen Honigsauger raigide, die Rohrdrossel (Calamoherpe syrinx), itirir und den Fliegenschnäpper (Rhipidura), temarubi.” [1]

translation:

“The bird world is richer by number and species, The frigate bird (Tachypetes aquila), itsi, the black tern (Anous), doror, the white tern (Gygis), dagiagia, are kept as pets; the first one was formerly considered a holy bird, with the two others are used for fighting games. At the beach one mets with the turnstone (Strepsilas interpres), dagiduba, the plover (Numenius), the sandpiper (Tringoides), ibibito, the snipe, ikirer, the curlew, ikiuoi, the beach rider [?] iuji, the rail, earero bauo and two gull species (Sterna), igogora and ederakui. In the bush one observes on the flowers of the coconut palm the small honeyeater raigide, the reed thrush (Calamoherpe syrinx), itirir and the flycatcher (Rhipidura), temarubi.“

These two accounts, made in the early 20th century both mention a form of rail that inhabited the island of Nauru; for biogeographical reasons, this almost certainly was a flightless endemic species, which is now extinct without leaving behind any traces.

*********************

References:

[1] Paul Hambruch: Nauru. Ergebnisse der Südsee-Expedition 1908-1910. II. Ethnographie: B. Mikronesien, Band 1.1 Halbband. Hamburg, Friedrichsen 1914

*********************

edited: 04.01.2024