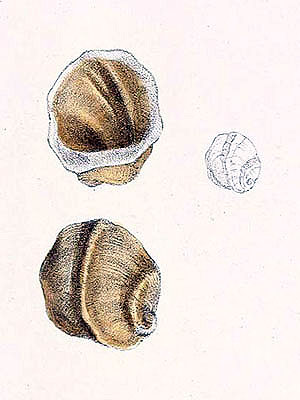

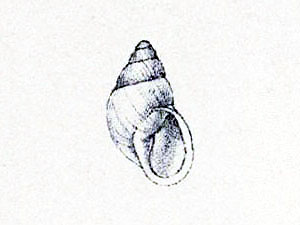

Ancey’s Taipidon Snail (Taipidon anceyana)

Ancey’s Taipidon Snail was endemic to the island of Hiva Oa, Marquesas, it was described in 1887 when the species apparently was still alive, the author gives some slight information about it.:

“Sa grande taille, son large ombilic, ses grandes lamelles aperturales blanches et bien visibles, empêcheront de confondre cette Espèce avec ses congénerès.“

translation:

“Its large size, its large umbilicus, and its large, white apertural lamellae, well visible, will prevent this species from being confused with its congeners.“

***

Ancey’s Taipidon Snail was apparently a lowland species and might already have been extinct at the time of its discovery.

As far as I know, only three specimens of the species remain today with the holotype reaching a heigth of 0,23 cm and 0,5 cm in diameter, it is furthermore light yellow-brown and decorated with irregular, reddish flammulations.

*********************

References:

[1] Andrew Garrett: Mollusques terrestres des Iles Marquises (Polynésie). Bulletins de la Société malacologique de France 4: 1-48. 1887

[2] Alan Solem: Endodontoid land snails from Pacific Islands (Mollusca: Pulmonata: Sigmurethra). Part I, Family Endodontidae. Field Museum of Natural History Chicago, Illinois 1976

*********************

edited: 20.04.2019